Zanele Muholi is a self-proclaimed ‘visual activist’. Born in Umlazi, Durban, Muholi now lives in Johannesburg and for more than a decade has aimed to exhibit a new democratic representation of South African LGBTI history.[1]

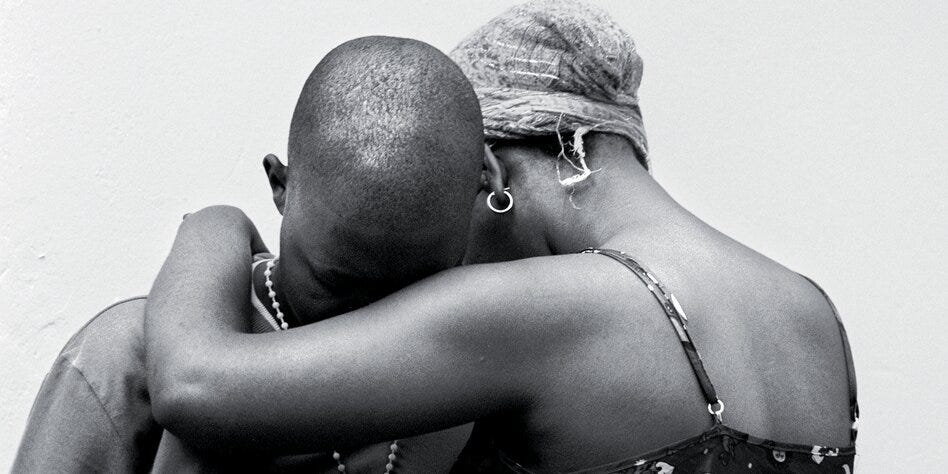

Zanele Muholi, Comfort, 2003

In colonised Africa, the black female body was subject to European interpretations as savage and sexually deviant. This colonising narrative continued in post-apartheid South Africa with undesirable representations of women presented in popular visual culture. The black female body was offered for examination and discrimination, but not given a voice. Muholi’s work challenges these inherited and existing ways of seeing the female body.

From 2002 - 2006, Muholi worked on their first photographic series Only Half the Picture. These early works attempt to raise awareness of sexual violence and rape in a society that silences it. Muholi addressed an absence with this pioneering work, as the issue of sexual abuse against black lesbian women was not publicly addressed when their work on the series began.[2]

In Only Half the Picture, each work focusses on fragments of the body.[3] As Otobong Nkanga argued the historical use of photographic fragments of the human body was a ‘scientific tool (…) to probe (and penetrate).[4] Muholi reappropriated this colonial tradition of depiction to tell a new contemporary story.

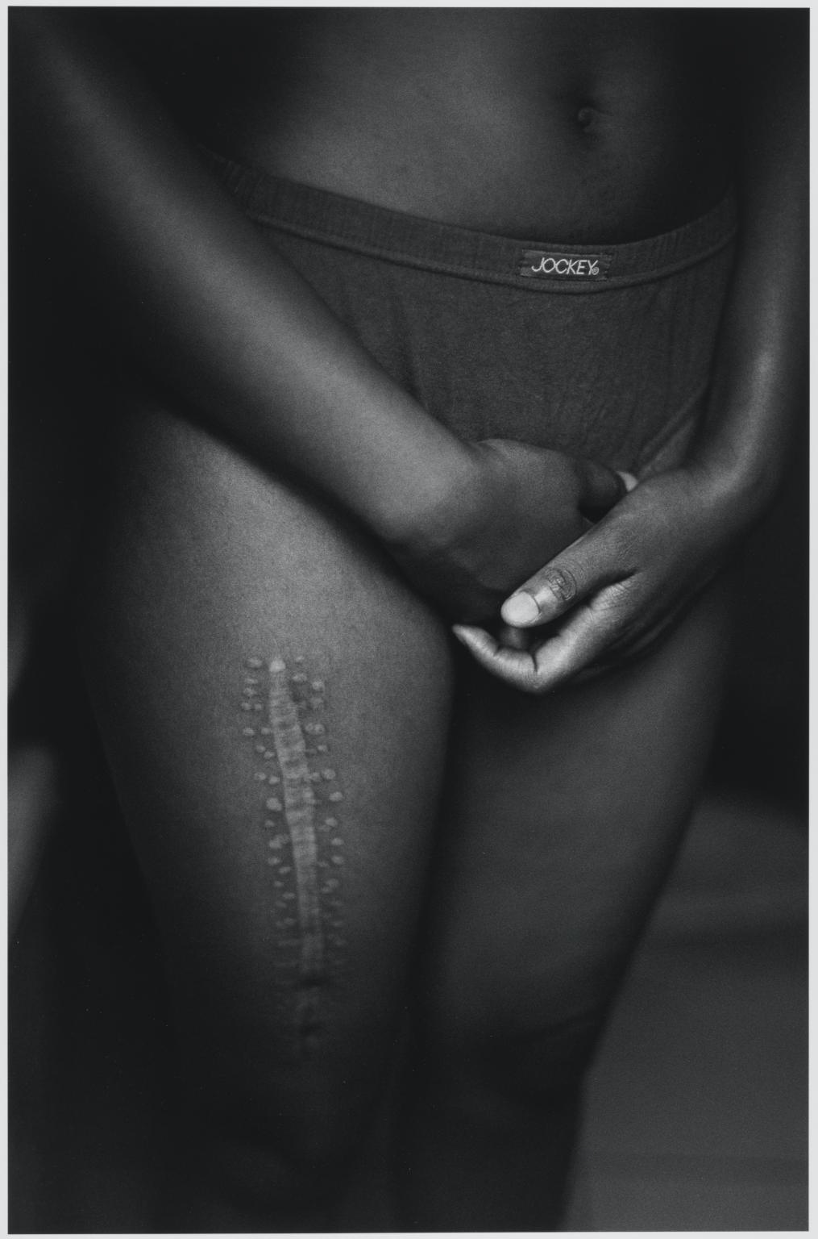

Zanele Muholi, Aftermath, 2004

One of the most iconic images from the series, Aftermath, 2004, shows the torso and thighs of a female in Jockey pants. Her hands are loosely interlinked in front of her covered genitalia, suggesting her vulnerability. The photograph was taken two days after the woman was raped but the focus on the scar on her right leg references a history of violence and trauma and its lasting impact.[5] African traditions of scarring signify fearlessness and bravery in men, but on women they symbolise contamination and loss of innocence.[6] The gender ambiguity suggested in Aftermath destabilises this symbol of revulsion in South African society, instead suggesting the quiet courage and power of the female depicted.

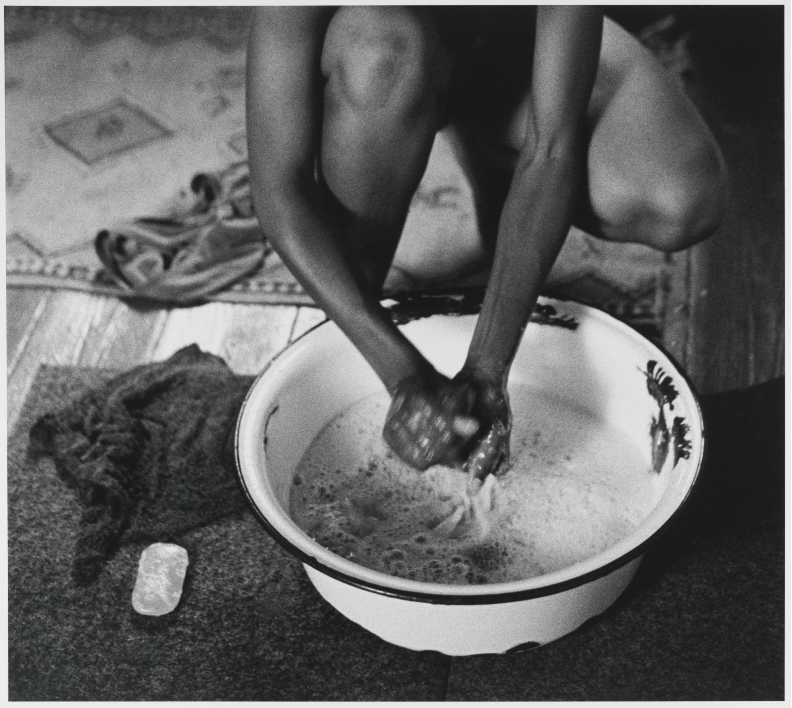

Zanele Muholi, Ordeal, 2003

Ordeal, 2003, portrays another ‘aftermath’ of rape and sexual violence. This image gives no visual clues of past violation but focusses on a woman bending over a bowl of water. Her hands are out of focus suggesting manic washing. Trauma is subtlety suggested through movement.

Many works protect the identity of the photographed subject as rarely faces are shown.[7] Anonymity achieves both a deeply personal depiction of a violated body, but also becomes representative of a wider patriarchal and hegemonic society of violence. Muholi’s ‘activism’ is to directly affect the viewer, forcing them to really see the subjects presented in a new and different way, thereby achieving a restorative political act.[8]

Zanele Muholi, Hate Crime Survivor / Case Number (diptych), 2004

Hate Crime Survivor / Case Number, 2004, is a diptych which juxtaposes a slip of paper detailing police case notes of a crime, ‘Rape + Assault GBH’, with an image of a woman’s hands resting on her lap. The image is closely cropped from waist to knees and focusses on the identity tags around her delicate wrists and the stripy hospital trousers with which she has been issued. The identity tags are undoubtedly reminiscent of manacles and handcuffs, relating to a past history of slavery, but also referencing contemporary accusations made against violated black lesbians that either their claims are untrue, or they are themselves responsible for provoking the attacks.[9]

Zanele Muholi, Beloved V, 2005

In contrast, intimate and sexual works from the series prove that life after trauma is not without desire and closeness and by portraying this positivity Muholi successfully ‘disrupts the perpetrator’.[10]

Working closely with the subjects of their images, Muholi gains trust by directly involving the people photographed and refers to them as ‘participants’.[11] Muholi has stated that they ‘record stories’ to avoid appropriation.[12] This reporting style subverts the action of photography which ‘captures’ a moment, appropriating the subject’s story and taking away their voice.

Muholi’s work directly contrasts with popular media images of black lesbians, which reinforces the negativity towards this community and often positions the subject as a victim. In addition, the insensitive journalistic objectification of named survivors of sexual violence and rape, facilitates an ongoing cycle of violence for both them and their families. Muholi subverts this stereotypical narrative, which allows their participants to achieve visibility in a positive and humanistic way, free of the usual distorted iconography.[13]

Muholi creates works which opens space for investigation, decentralising historical narratives which traditionally established representations of sexuality, gender, and race.[14]

This article was adapted from research and writing conducted for my MA dissertation, African Diaspora Women as Spectacle: Exhibiting Photography of Sexual Violence in London, UK, (September 2021).

[1] Yancey Richardson, Artists, Zanele Muholi, Biography, https://www.yanceyrichardson.com/artists/zanele-muholi (visited 8 June 2021).

[2] Brenna M. Munro, ‘Queer Citizenship, Queer Exile: K. Sello Duiker and Zanele Muholi’, in South Africa and the Dream of Love to Come: Queer Sexuality and the Struggle for Freedom, (United States of America: University of Minnesota Press, 2012), pp. 198-233, (p. 222).

[3] Nomusa M. Makhubu, ‘Violence and the cultural logics of pain: representations of sexuality in the work of Nicholas Hlobo and Zanele Muholi’, in Critical Arts, Vol. 26, No. 4, (October 2012), pp. 504-524, (p. 509).

[4] Quoted in Clémentine Deliss, The Metabolic Museum, (Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 2020), p. 46, originally quoted in, Foreign Exchange, (or stories you wouldn’t tell a stranger), (exhibition catalogue, Weltkulturen Museum Frankfurt am Main, 2014), eds. Clémentine Deliss and Yvette Mutumba, (Zurich, 2014).

[5] Natasha Bissonauth, ‘Zanele Muholi’s Affective Appeal to Act’, in Photography & Culture, Volume 7, Issue 3, (November 2014), pp. 239-252, (p. 245).

[6] Makhubu, (2012), p. 509.

[7] Makhubu, (2012), p. 509.

[8] Bissonauth, (2014), p. 240.

[9] Kylie Thomas, ‘Zanele Muholi’s Intimate Archive: Photography and Post-apartheid Lesbian Lives’, in Safundi, Vol. 11, No. 4, (2010), pp. 421-436, (p. 429).

[10] Stephanie Selvick, ‘Positive Bleeding: Violence and Desire in Works by Mlu Zondi, Zanele Muholi, and Makhosazana Xaba’, in Safundi: The Journal of South African and American Studies, Vol. 16, No. 4, (2015), pp. 443-465, (p. 461).

[11] Bissonauth, (2014), p. 241.

[12] Gabeba Baderoon, ‘“Gender within Gender”: Zanele Muholi’s Images of Trans Being and Becoming’, in Feminist Studies, Vol. 37, No. 2, (Summer 2011), pp. 390-416, (p. 405).

[13] Z’étoile Imma, ‘(Re)visualizing Black lesbian lives, (trans)masculinity, and township space in the documentary work of Zanele Muholi’, in Journal of Lesbian Studies, Vol. 21, No. 2, (2017), pp. 219-241, (p.

228).

[14] Raél Jero Salley, ‘Gender and South Africa: Zanele Muholi’s Elements of Survival’, in African Arts, Vol. 45, No. 4, (Winter 2012), pp. 58-69, (p; 62).