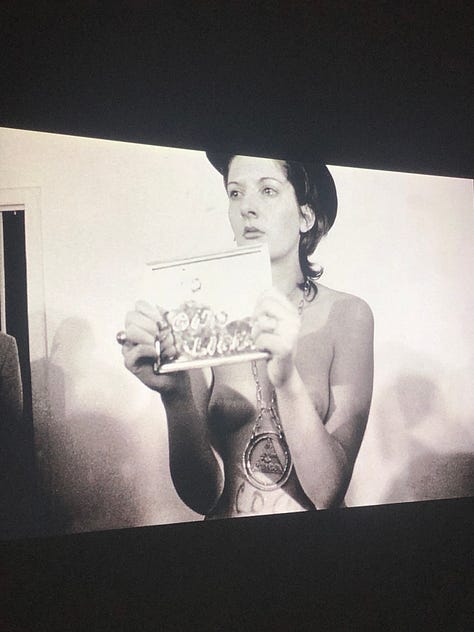

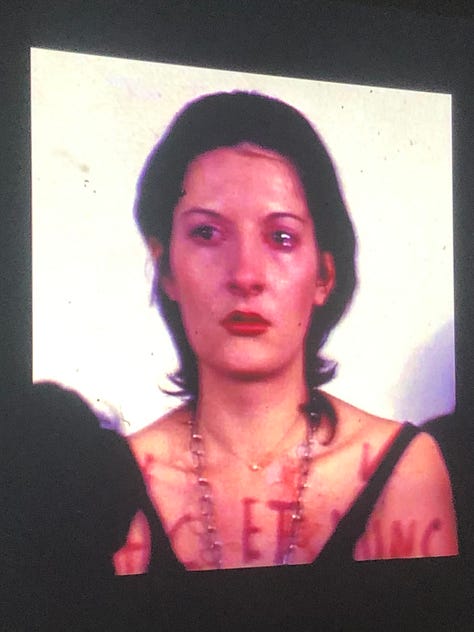

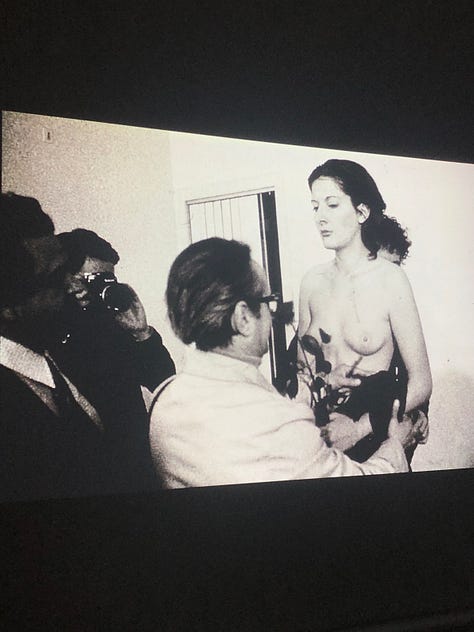

Standing in the cool galleries of the Royal Academy, London, with its marble columned doorways, and beautiful high ceilings, I was transfixed, as I watched images of a young Marina Abramović, projected against the stark white walls. The exhibition was buzzing with crowds of people. As the images absorbed me, the sounds of the public faded, disappearing into a hum beyond the rhythmic click, click, click of the slide machines. I looked at the young artist, one image after the other, tears in her eyes, subject to violence, humiliation, and betrayal. Interjected between these images were others of leering men, a crowd more like a mob, and fascinated, smiling, and laughing participants. The documentary photographs are from the work, a performance piece from 1974 where the artist presented herself as an object and invited a crowd of people to use her as they wished during the six-hour long performance, along with a choice of props from a table of 72 items referencing either pain or pleasure.

The images are difficult to look at. The artist was wrapped in chains, written on in lipstick, stripped to her waist, her breasts exposed. The crowd committed countless violent acts against her, they cut her skin, made her bleed, drank her blood, and sexually assaulted her. Very few of the photographs showed acts of kindness, none showed love for another human being. The work is a stark reminder of the cruelty of humans, and the violence which we are so quick to inflict on each other. I couldn’t help but wonder if the participants were also more willing to act violently towards a woman? At the end of the gallery, the table of objects from the performance was on display, and I stood almost alone watching the documentary slide show projected around the side walls of the gallery, while visitors crowded around the central table, queuing and jostling to witness and photograph the props on display. The fascination with the objects, over and above the documentation of the actual performance, only reinforces the attitude that must have been present in 1974, and how quickly people would be to use these objects, especially when given permission.

In 2023, it seems almost incomprehensible that the Royal Academy, London is presenting its first solo retrospective by a female artist. Marina Abramović, currently on display at the Royal Academy, London, is the first female artist to be offered a solo show in the main galleries in its 255-year history. The exhibition presents key works by the artist and spans her successful career over the last 50 years. Works such as Rhythm 0, prove why Abramović is celebrated as a conceptual and performance artist, known especially for her endurance art, and recognised as a world icon in her field.

The exhibition begins with documentation from one of Abramović’s later performances, The Artist is Present, 2010, in which the artist sat at a table for three months in MoMA, New York and invited visitors to sit opposite her, and meet her gaze, for a duration of their choosing. One wall of the London gallery, is covered in a multitude of videos of the artist’s face, arranged in blocks of colour, according to the outfit she wore, one white section, one red section, and one black section. On the opposite wall, the video monitors show the guests sat facing her. The presentation is a fascinating, overwhelming glimpse of an originally slow and mindful performance. Abramović stares intently, looks sleepy, leans forward, smiles ever so slightly, looks questioningly, and sometimes bored, while the visitors mostly look serious, like they are completing a test, a few smile, and some overwhelmed by the experience, cry. This more familiar portrayal of the artist and her work, leads to the violent Rhythm 0 documentation in the second gallery, and reinforces Abramović’s vital concept of the audience as a fundamental and active participant in her work. An experience that extends even to later audiences witnessing original performances.

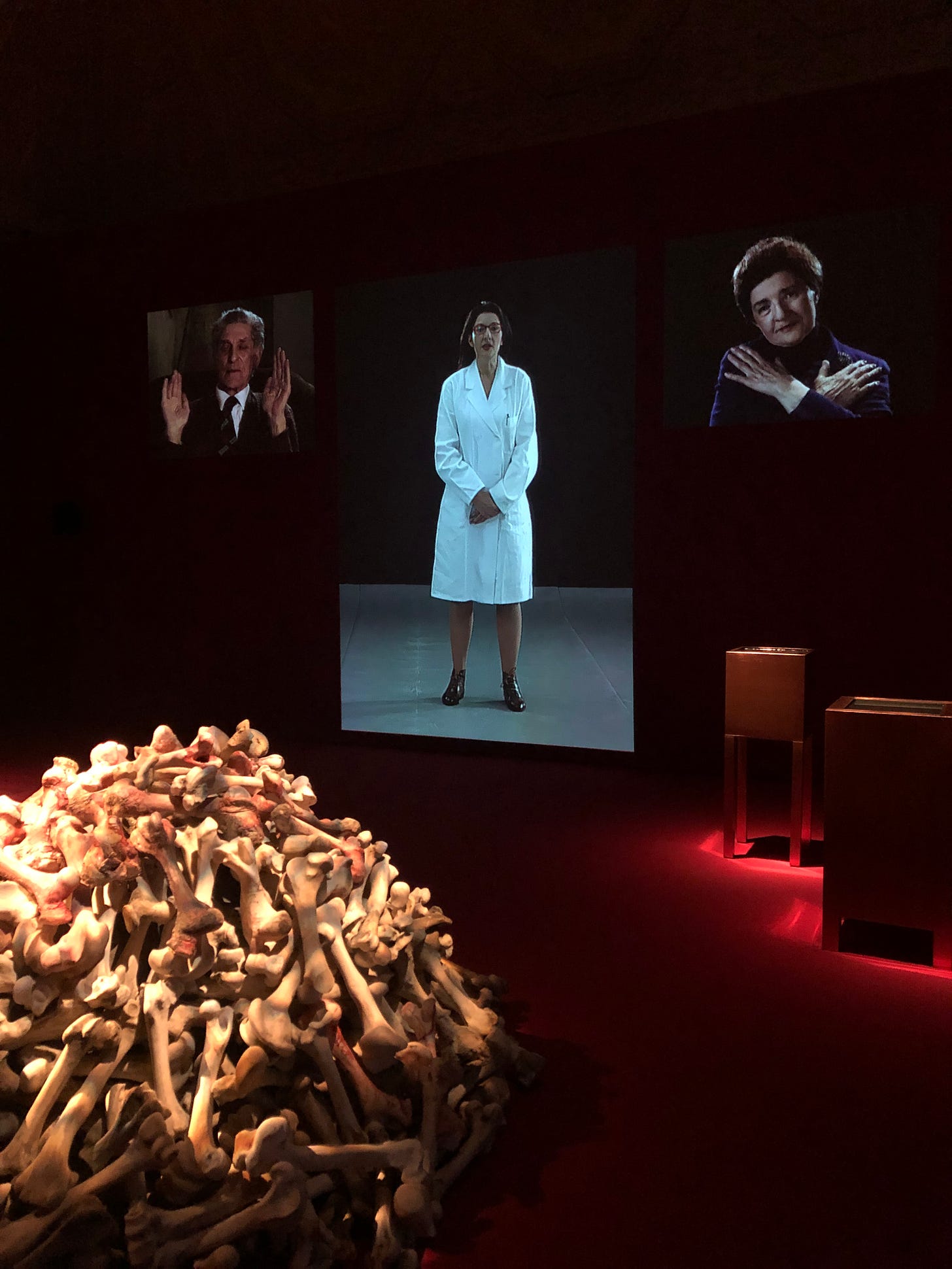

In a room with salient red walls, a huge pile of bones is stacked in the centre of the room. Behind the bones, a multi-channel video plays, and the artist, flanked by her parents, tells a gruesome folk story about the ‘wolf rat’. This installation is the documentation from the performance Balkan Baroque 1997, a 4-day, 6-hour performance conceived for the Venice Biennale. Abramović’s voice fills the claustrophobic, blood-like space, and recounts how in the Balkans they kill rats, catching them, giving them only water, as they face suffocation from their teeth growing too long. At a desperate point, the weak ones are killed one by one, until only the strongest remains. Now the rat catcher, just half an hour before the rat will suffocate from its overgrown teeth, takes a knife and cuts out its eyes, releasing it back into the wild. The terrified rat runs around blindly killing other rats, before a stronger one takes his life. ‘This is the way how we in Balkan make wolf rat’, Abramović tells her audience, at which point she throws off her white lab coat and dances to a suggestive Balkan song. The bones in the room are those she attempted to wash clean during her performance in Venice. Developed to represent Yugoslavia at the Biennale, organisers were so shocked by the anti-nationalistic message that Abramović was forced to perform her piece in the basement of the Italian pavilion instead, for which she was awarded the Golden Lion. Black and white photographs document her performance Rhythm 5, 1974, showing a large wooden 5-pointed star, which the artist set alight and lay inside, causing her to faint and need to be rescued. Another photograph shows the 5-pointed star burnt into the skin of her stomach for the performance Lips of Thomas, 1975. Abramović references her close connection to her cultural heritage and the influence it has had on her, exploring Communism, and extremes of violence and eroticism, all bound up in Balkan identity. After her father died, the artist made The Hero, 2001, in which she sits upon a white horse, looking into the distance, a white flag blowing in the wind, and the Yugoslavian national anthem being sung.

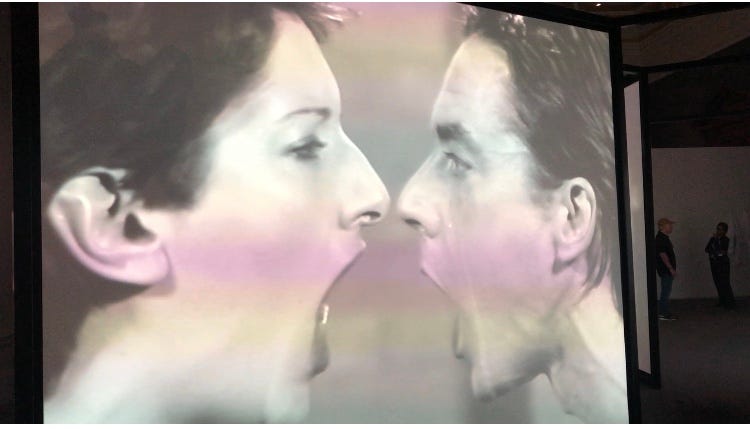

In a subsequent gallery, Abramović’s exhibition progresses into a display of later Rhythm works, joint explorations with her partner and lover, Ulay. The pair cause each other fear, they shake, they kiss, they slap each other’s faces, and they scream, and scream, and scream. The screams echo around the gallery and permeate every other work. The cacophony of video projections is an overwhelming insight into human emotion, pain, violence, pleasure, and dependency on one another. To the left of the doorway into the next gallery, is a small tv screen, showing video documentation of Ulay and Abramović’s performance, Imponderabilia, 1977, in which the artists’ naked bodies half block a doorway, and embarrassed and mostly hurried guests squeeze between them, all appearing oblivious to their brushing up against nudity. The performance is re-enacted by young performance artists at specific times during the London exhibition, only in this case, an alternate doorway is presented for guests wishing to bypass the experience. Instead of walking between the male and female naked bodies, I decided to watch visitors interacting with this performance work. Several decades later, visitors are given a choice to take part, which alters the experience of the original performance, but one of the most fascinating aspects of the piece was watching which performance artist the visitor would turn towards to squeeze through the space. In the time I watched not one man turned towards the male. The naked female performance artist was roughly and crudely rubbed against by every male visitor, one older male stopping afterwards, a little way through the doorway, to blatantly stand and stare at her genitals. Only two young women, turned towards the male performance artist, brushing against his body and looking into his face, as they passed through. All the other women, especially the older women, faced the female, and gently side-stepped through the tight space.

When Marina and Ulay realised their love was over, their art stopped focussing on human interaction, and after briefly working with objects, Abramović focussed on her body’s connection with nature, and the natural world. It is interesting how the progression of works on display highlight how young bodies strive for human connection, physical presence, solace in the romantic connection with another. Our older bodies have learnt to be comfortable, to recognise oneself, to accept the trauma, the change, the loss, and embrace feelings. Those feelings are only amplified when surrounded by nature, a reminder of how small and temporal we are within the huge footprint of the natural world and all its wonders. The Lovers, Great Wall Walk, 1988 was Ulay and Abramović’s final performance. Walking from either end of the Great Wall of China, the pair originally intended to get married when they met in the middle, but by the time of conception they used the work to say a final goodbye as they ended their relationship. After the intensity of the previous performance works, this work invoked sadness in me as I watched the solitary figures walking alone. Great wall rubbings from the performance fill the sombre gallery wall opposite, and a final dedication to Ulay, who died on 2 March 2020, completes and concludes the series of works.

Following the ‘Great Wall Walk’ and her split from Ulay, Abramović spent many years investigating immaterial energy. Having used her physical body in her performance art from the beginning of her career, the artist now wanted to create an immaterial transmission of the artist’s experience to the audience in an immaterial way. Abramović stated, ‘Immaterial art is the strongest because there’s no obstacle; there’s just energy, and I believe in energy.’ In the series of works, The Transitory Objects for Human Use, Abramović created works which placed the audience participants at the centre of the work, and removed the presence of the artist. The ‘Transitory Objects’ allow the participant to access the curative power of energy from crystals and metal, as used in traditional Chinese medicine. Visitors sit on, lay on, and press their foreheads, chests, and genitals against cold stone and metal, exposing themselves to a mindful moment in a busy gallery, experiencing a carefully curated encounter by an absent artist. Abramović suggests an experience and invites the visitor to take part, only this time the participant must use their own body and escape the emotion and violence of life, so clearly depicted and exposed in the artist’s early works, allowing themselves to undergo a transformation.

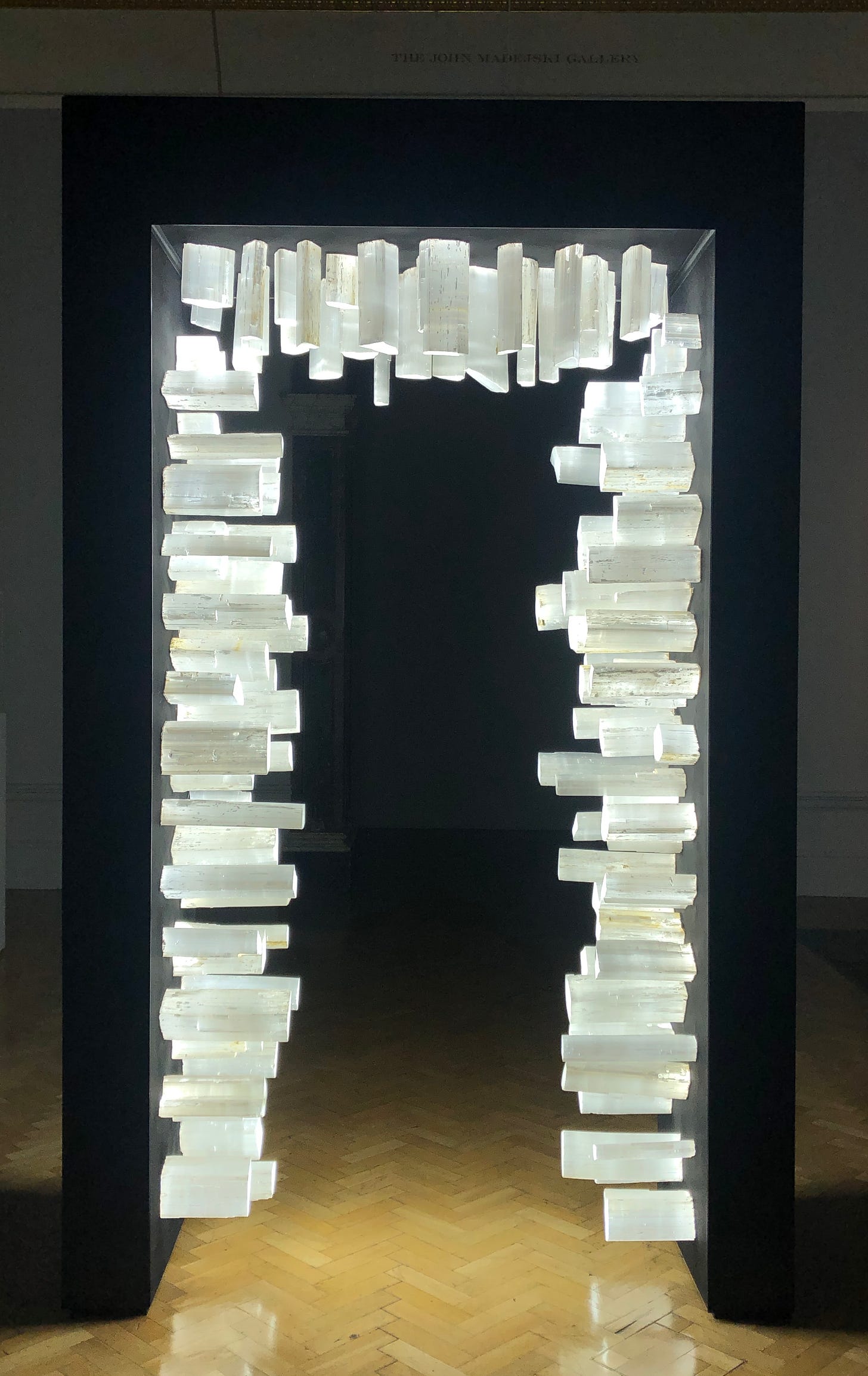

In no other work is the concept of transformation more focused than Abramović’s Portal, 2022. The large rectangular doorway with its deep black outline, glows on the inside with thick luminous selenite crystals. The crystals emit an unexpected heat. As you walk through you are blinded by the brightness of the light, forced to close your eyes momentarily and experience nothing but the sensation of the radiant heat warming your skin. When you emerge the other side, a chill hits you. You can open your eyes again. You really do feel like your body has travelled. The artist believes to walk through the portal is to change your state of consciousness, but as the interpretation board suggests, every day we move through a series of thresholds changing between different states of being, and moving between different experiences. This experience forces you to recognise this sensation, prompting a change of state, an unexpected mindful encounter that grounds you in your body. It is a treat to be prompted to recognise this and feels like an almost spiritual experience.

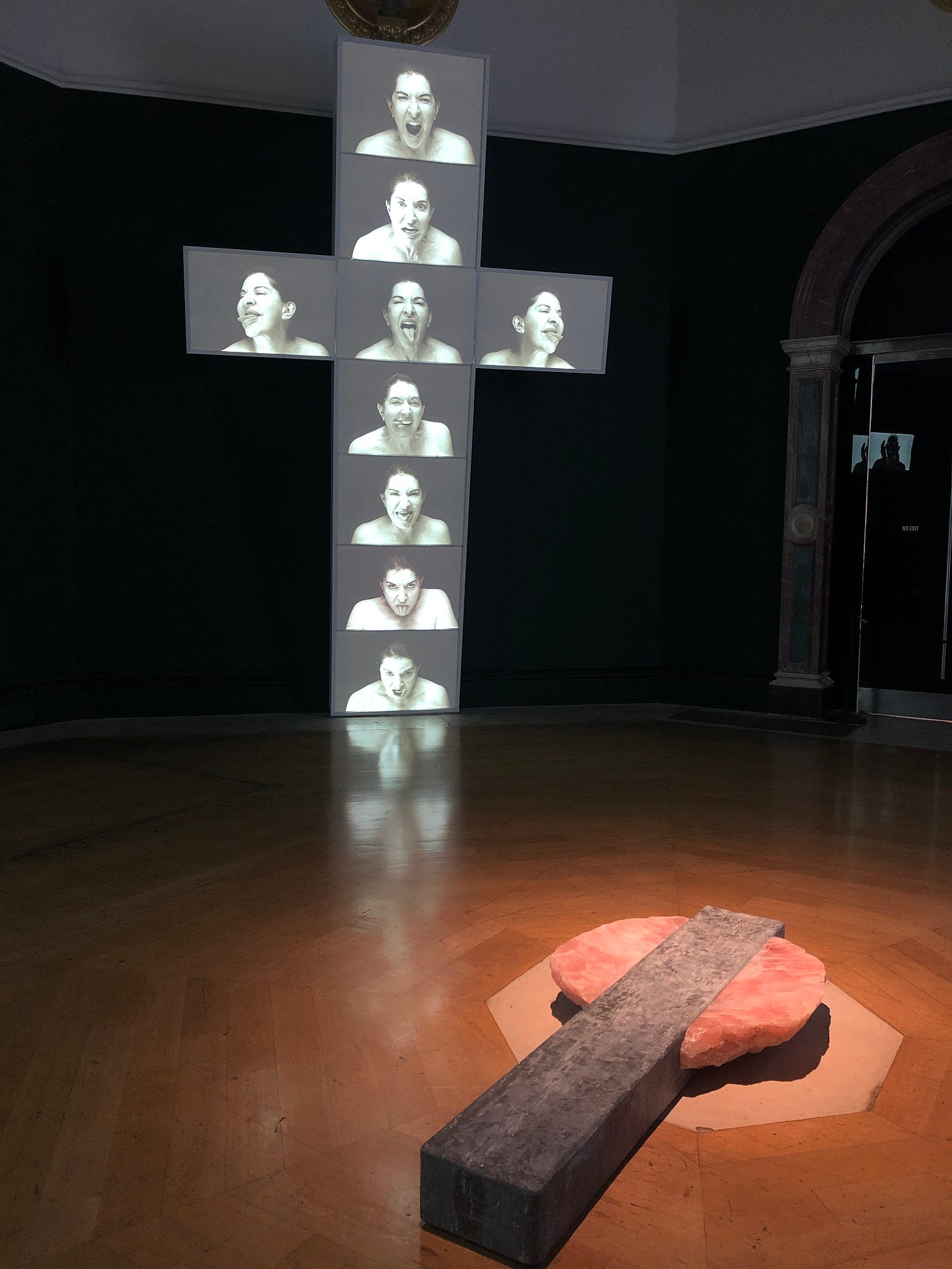

Among the participatory objects and portals, Abramović remains very present in the galleries in documentation from a multitude of performances. In Dragon Head, 1990, a snake slowly slithers across the artist’s face, distorting her features. The artist sleeps beneath a Banyan Tree, she touches her tongue against a rock on a windy beach, she walks among the trees in the park, she submerges herself in crystals, she lays beneath a stormy sky, and on the edge of an ocean with waves lapping closer and closer, works which she explains as playing with the limits of her consciousness. In her later works the foreshadowing of death is ever present, and the artist memorialises herself and the many extremes of human emotion in alabaster slabs in The Five Stages of Maya Dance, 2013/16, and in large photographic images set in four enormous crosses, set out in a circular room, surrounding a cross made of crystal laying on the floor in the centre, in a tomb-like installation. These works culminate in the performance, Nude with Skeleton, 2002/2005/2023, in London a live performance with a young performance artist, laying on a slab with a skeleton on top of her naked body, juxtaposed with a video of Abramović’s original performance beneath. This dual presentation doubly echoes and reminds the viewer of the transitory state of being, the states of life and death, and the precarious and subtle transition between these two states.

In the final gallery, the exhibition concludes with one of the artist’s most well-known performance works, The House with the Ocean View, 2002/2023. Originally performed by the artist in Sean Kelly Gallery, New York for a duration of 12 days, the artist resided in three specifically constructed living units in the gallery space, abiding by self-imposed rules of not eating and not speaking, creating a connection with audience members who came to watch. Arguably the most arduous of all of Abramović’s performance works, the London exhibition presents the performance piece on three different sets of dates with three different performance artists. While visitors intently watched the performance artist, walk the space, use the toilet, and sit silently, I was fascinated by the ladders that led from the gallery floor to each living unit. The steps were made of sharp knives, all blades facing upwards, presenting an impossible escape from a self-imposed containment, a final reminder of Abramović’s comment on the violence of the state of living, connecting, and being.

Abramović’s exhibition is a celebration of her legacy as a brave artist who has pushed her mind, body, and artistic practice to the extreme. She truly merits her reputation as a formidable performance and endurance artist. This well-deserved retrospective of Marina Abramović is not to be missed.

Marina Abramović is on display at the Royal Academy, London, UK until 1 January 2024.

All photographs are my own.